Torah Study Date

Saturday, April 15, 2023

Verses Covered

Exodus (Sh’mot) 6:6-13

Next Session

Saturday, April 22, 2023

Starting at Exodus 6:14

Last week we had a wide-ranging discussion of interpretive methodology. We discussed Exodus being the oldest book of the Torah and the idea that Exodus does not know Genesis but Genesis knows Exodus, indicating Genesis was composed later. We discussed the idea, held by many, that the exodus from Egypt did not happen and considered what about the story makes it universally applicable. We considered the Torah as a literary text and Exodus, specifically, as a text about everyone who has been enslaved and then becomes free or who has not been able to be what they need to be and then gains that ability. The story has broad appeal because everyone has such experiences. As an example of a contemporary literary text, we discussed Star Wars being an antifascist fiction—a work of fiction, but still meaningful.

We also discussed there being two founding stories in the Torah, the patriarchal story in Genesis and the Exodus story, and the idea that some stories in the Torah combine two different stories to make one story that will appeal to two different actually existing groups because elements of the story of each group appear in it. As a comparison, we considered the 1619 Project as an effort to create an overarching story of U.S. history that includes both black and white origins (1619 and 1776). We discussed the concrete bodily references in the Torah (often overlooked in translation), for example, in our reading for the week, that YHVH would redeem the Israelites with an outstretched arm and that YHVH had raised his hand to give the land to Abraham (meaning had promised the land to Abraham). Thank you to R. Sara for these, and many other, insights into different ways of reading and thinking about Torah, i.e., different Torah study methodologies.

We discussed YHVH’s four redemptive assertions–I will bring you out, I will rescue you, I will redeem you, I will take you to me as a people and become your God (emphasis through repetition—which we’ve seen before in Exodus)–and YHVH stating that they will know that “I am YHVH, your god” who is doing all of that. We considered the idea that YHVH becoming known is a main theme of Exodus. We discussed YHVH being reintroduced to the Israelites after 400 years—the long period in which the Israelites were in exile—and that the Israelites did not know or did not remember YHVH. We discussed the object-relational component of the story—does YHVH still exist after all that time of absence (like a child learning that their parent still exists even though they are gone for a time)?

We discussed Moses telling this to the Israelites but them not hearing him due to their shortness of breath/crushed spirit and hard labor (shortness of breath being another concrete bodily description that resonates both on the bodily level and on the spiritual level) and YHVH responding by telling him to come and speak to Pharaoh telling him to let the children of Israel go. We then discussed Moses’ response: that, if the children of Israel would not listen to Moses, why should he think that Pharaoh would listen to him (noting the kal vachomer (lenient and strict) argument that has the form: if the easier is not possible, why would the harder be possible?) and that he is uncircumcised of lips (another concrete bodily term that indicates something more general, namely, that there is something that impedes his speech). We discussed the word for circumcision there (aral) and noted that there is another word for circumcision (milah) used in other places and the view, that we did not necessarily endorse, that lack of circumcision indicates some kind of ritual unfitness on Moses’ part. We noted that YHVH seems unmoved by Moses’ concerns but does go on to include not just Moses but also Aaron in his exhortation to bring the children of Israel out of Egypt, perhaps reminding Moses that he will not have to do it alone. We empathized with Moses being uncertain that he could have an impact on Pharaoh noting that it is about as likely an African going to the President of the U.S. during slavery, asking for and getting the Africans back.

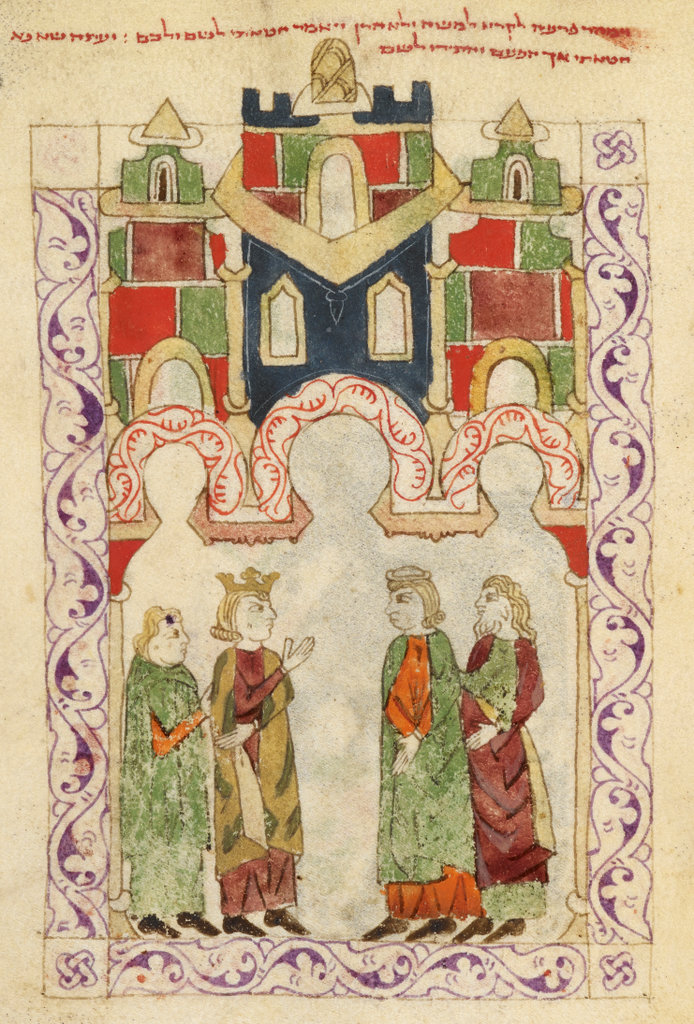

Our artwork this week is more from the illuminated Hispano-Moresque Haggadah (Hispano-Moresque = Spanish-Moorish, the Moors being Arab or Berber Muslims from North Africa) (c. 1300), Moses and Aaron Asking Pharaoh to Let the Israelites Leave Egypt (above), and The Plague of Frogs (below). The illustrations are a lovely combination of abstraction, repetitive design, and playful representations of people and animals. Notice that two of the frogs in the plague story end up caught in the Moorish framing design adding a drole and self-conscious touch.