Torah Study Date

Saturday, October 7, 2023

Verses Covered

Exodus (Sh’mot) 13:3-13:16

Next Session

Saturday, October 21, 2023

Starting at Exodus 13:17

We opened our session with verse 13:3 and immediately noticed an odd shift to the future. Moses was explaining why we celebrate the feast of Passover, when in fact in our narrative the Jews had only just left Egypt. This is also the verse in which “with a mighty hand”, which we recognize from the Passover Haggadah, is used for the first time in Torah. In verse 4 we pointed out that Aviv is not a Jewish month; it means “spring” in Hebrew, from the root “grain”. We also noted that the verse starts with the word “hayom” or “today”, indicating emphasis.

Verse 5 mentions a big list of people inhabiting Canaan, not just the Canaanites. The population of Canaan was diverse. Many cultures were mingling there because it was located on a major trade route. We noted that the word “avodah” is repeated twice (in slightly different forms), meaning “worship, sacrifice, service”. The Israelites were now God’s servants and no longer Egypt’s servants/slaves. Verse 6 is basically a repetition of what we have already read, with the addition of the word “chag” which is a later technical term for a pilgrimage festival.

Rabbi Myra pointed out that verse 7 is in the passive voice, as if the leavening, the “chametz” is the actor. We also wondered about the significance of the seven days. Was it related to hurrying? Was it related to the 7 days of creation? Laura brought up that leavening in those days was natural yeast, which was always present in the air. Therefore, the Israelites must have been in a constant rush to bake their dough before it rose. In observing the holiday prohibition against leavening, the Israelites were reenacting the hurrying of their ancestors during the Exodus. This active commemoration is to demonstrate that they are no longer slaves in Egypt; they serve the Lord instead.

Verse 9 seemed very odd indeed to us. What are the “signs” that the people should place on their hands and between their eyes? Rabbi Sara explained that the Deuteronomic redactor placed this verse here. Today we immediately think of tefillin, little boxes with passages from Deuteronomy inserted in them, but these boxes were invented much later during the Second Temple period. (Thank you, Jacqui, for researching this for us.)

Rabbi Sara explained that the books of Genesis and Exodus were “out there” circulating in the culture, and we assume that a redactor/editor stitched them together into a cohesive narrative. In Exodus, this editor was concerned with institutionalizing the practice of Judaism, teaching it to future generations, and codifying the observance of religious holidays. The language is often an indication that the redactor is inserting himself, for example the word “l’ma’an” – “in order that…” is very common in Deuteronomy.

Verse 10 continues in the redactor’s voice, and Verse 11 is a repeat of Verse 5, but leaving out all the other cultures except the Canaanites. Verse 12 repeats verse 13:1, about the first issue of the womb being for the Lord, but uses the word “sheger”, which is found all over the book of Deuteronomy, giving us another clue pointing to the author. Verse 13 brings in a new idea – that one can redeem a first-born donkey with a sheep. We discussed how important donkeys were for transportation and work. It would make sense to preserve them for that purpose. On the other hand, one must also redeem a first-born son. The text presents no way to do that.

Verse 14 reiterates that all these customs are because Adonai liberated us from Egypt. We have institutionalized gratitude for the firstborn. In verse 15 we are asked to sacrifice in memory of the slaughter of the firstborn and redeem our sons. We wondered what happened to the sacrifices, considering that during this time there were no priests yet. Rabbi Sara suggested that most likely they ate the useful parts and burned the rest as a holy sacrifice. This practice is a change from Chapter 12. We pointed out that getting rid of males in a flock of animals is practical since a herder only needs one male in a flock for reproduction. Verse 16 ends Parasha Bo with another mention of tefillin.

We concluded our session with another discussion of Exodus and how different it is from Genesis, with its straightforward stories/narratives. Exodus, in contrast, has multiple layers, multiple authors, many repetitions, and many insertions into the narrative. This book demonstrates the “documentary hypothesis” (i.e. that the Torah was written by many different authors) but the identity of each strand is not as neat as was first thought.

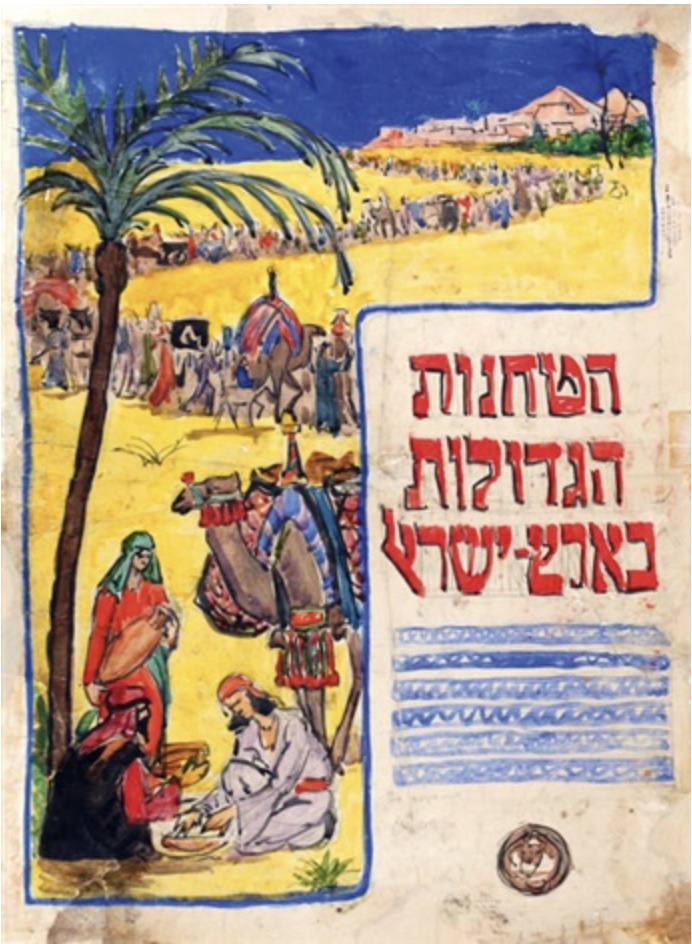

Our artwork this week is by Polish-Jewish Israeli artist, Ze’ev Raban (1890-1970), Leaving Egypt (preparatory drawing) and Escape from Egypt (haggadah). Raban was a leading figure in the Bezalel School of Art that combined European art nouveau with traditional Persian and Syrian art styles. He studied in Munich, Paris, and Brussels and in 1912 moved to mandatory Palestine where he joined the Bezalel School of Art. Each of our artworks shows the Israelites leaving Egypt, the first work being a delightful preparatory drawing showing the Israelites with their burdens accompanied by birds, oxen, goats, and camels and the second being a more richly colored version of the event zeroing in on a few people in the foreground while showing the long line of others in the background.