Torah Study Date

Saturday, May 25, 2024

Verses Covered

Exodus (Sh’mot) 22:25-23:1

Next Session

Saturday, June 1, 2024

Starting at Exodus 23:2

Last week we had an interesting discussion about the law requiring that a garment taken as a pledge be returned before sunset. We assumed it means that, if you lend money (or an item) to someone and take the person’s garment as a pledge or surety for the money (or item), you must not keep it longer than that day (the Hebrew day ending at sunset). We talked about God saying that the garment is what covers the skin and that, without it, the person will not have anything to sleep in. We thought the law refers to a large garment that would be wrapped around a person and, at night, would be used to sleep in. We also assumed that the person referred to is one who has no other garment (since God says they will not have anything else to sleep in).

Laura discussed seeing a whole group of people in India sleeping in a similar garment at night—and that it even covered their heads. We referred back to R. Sara’s comment on the mishpatim protecting the vulnerable and noted that the reference to skin is about vulnerability. Skin can get scratched, cut, wet, wounded, sunburned, etc. It connects us to what is outside us. We noted that this mishpat (law) indicates that sometimes you should not demand what you deserve or are owed—since you are in fact owed something but the demand for it would leave a person completely undefended.

We noted that if the person whose cloak is not returned cries out to God, God will listen to or pay heed because God is gracious. We wondered what listening or heeding actually means in the context (no conclusion) and what it means for God to be gracious. I mentioned the liturgical phrase “grace, kindness and compassion” used to describe God (chen, chesed, rachamim). Writing this description, it occurs to me that not suspending a law or requirement might be a prime type of grace (or kindness or compassion). Here we are learning about law but also about its gracious or compassionate suspension in some cases.

We then discussed not reviling God or cursing a prince/chieftain among the people. We noted how different this is from what has preceded. From protecting the vulnerable to respecting God and leaders. We thought the aim of this mishpat is to keep the community together. We discussed limitations on this in cases of leaders that are so bad that a line is crossed.

We had a long discussion about not being hesitant to give the first fruits or the first-born son. We noted the son would be given to be a priest—and that later the son would be ransomed for a sum (pidyon ha ben) that would be given to the priests instead of literally the son being given away to the priests. We discussed how hard it is to give up the first produce of labors (agricultural or familial). We noted the idea of giving up for the sake of the community. We noted the same requirement regarding cattle and flocks, namely, that the first-born must be given up to God, presumably for sacrifice.

We discussed the two sentences stating, first, that you shall be a holy people to God and, second, that you shall not eat flesh torn by beasts in the field but throw it to the dogs. We noted Alter mentioning the low opinion of dogs in Torah. I noted that there is a more positive reference to them, specifically, when they do not bark on the night that the Israelites were going to leave Egypt. We discussed the question whether being holy refers simply to the commandments or is a separate commandment in itself. Are you holy by fulfilling the commandments? Or is being holy a different commandment? I mentioned Rabbi Morris Panitz, at IKAR in Los Angeles, recently suggesting that it is a different one. On his interpretation, since the holy is what is separate, the command to be holy means to look at what is beyond or separate from the (other) commandments. To look for something not written in the laws and that, as a result, you might not expect and, therefore, not see. R. Panitz was not referring to this particular passage, though (but a different one commanding holiness) and we tended to think that here the holiness command had to do with holiness about eating.

We discussed not carrying false reports or joining with bad people in acting as a violent or malevolent witness. We noted that this also is a different kind of commandment, specifically one that has to do with judgments and something like truth. We related this, once again, to keeping the community together. We had a long discussion about gossip, specifically the kind of gossip in which false or even just bad things are said about others. Carol mentioned the importance to the Chasidim of not carrying that kind of gossip. Ina mentioned the problem of social networks carrying false reports and we discussed at length the fact that such new communication technology magnifies the problem discussed in our passage. We discussed the need for educating young people on how to assess sources of social media information (as well as discussing political polarization).

Along the way, we discussed the fact that scholars do not really know exactly what the verse about first fruits says (“Everyone is unsure of what this means,” according to Friedman) and that the “indeed” in the verse about giving the cloak back comes from the repetition of havol, the Hebrew word meaning “to bind” (an example of emphasis by repetition of a word).

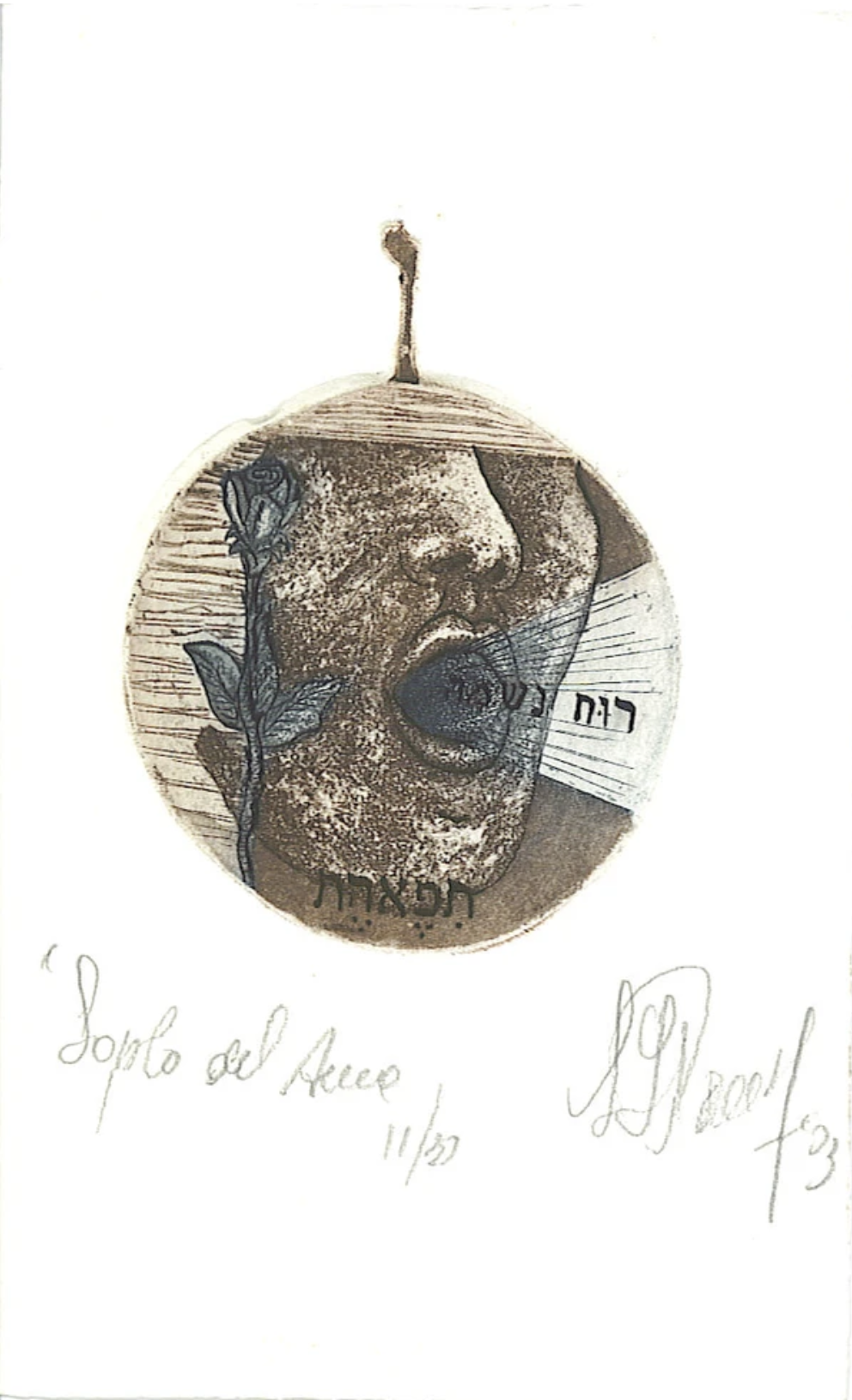

Our artwork this week is by Argentinian-Israeli Jewish artist, Lidia Rozanski, Mishpatim (above) and Soplo de Alma (Ruach ha Neshamah)/Tiferet (below). Mishpatim (etching with oil-based inks) is from The Women of the Book, a project in which a different Jewish woman artist illustrates each Torah portion (parsha). Soplo de Alma is from Rozanski’s illustrations of the Sefirot.

The web in Mishpatim (above) indicates women’s weaving. In weaving, Rozanski says, women both stay within the limits of mishpat’s traditional gender roles and transcend them by doing what they want in doing something creative. For her, traditional embroidery by women is prayer that commemorates different cultures. Rozanski was born and raised in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She studied architecture at the University of Buenos Aires and printmaking at Buenos Aires’ School of Fine Arts. She moved to Israel in 2001.