Torah Study Date

Saturday, June 8, 2024

Verses Covered

Exodus (Sh’mot) 23:8-23:17

Next Session

Saturday, June 15, 2024

Starting at Exodus 23:18

Last week we discussed the prohibition on oppressing the stranger or sojourner (ger) for you know the feelings (nefesh) of the stranger since you were strangers in the land of Egypt (Exodus 23:9). We noted that oppressing the stranger was prohibited also at Exodus 22:20. We discussed R. Myra’s idea that a ger is someone Jewish adjacent (thus bringing the ancient concept into a modern formulation), for example, someone living with you for a short time, someone who lives in your area but is not an Israelite, etc. We discussed the word translated as “soul” or “feelings,” namely, nefesh. Its early meaning is life, breath, that is, the part of/type of soul associated with life and living. It can extend to mean “feelings” since feelings and emotions are responses we have to our lived experience (and our sensory experience). We discussed the mishpatim (laws) applying to more and more groups—the stronger or more powerful, the weak or poor, even the enemy, and here and in the previous verse the stranger, sojourner or Jewish adjacent. We noted that the law gives a reason, namely, because you know the feelings of the stranger since you were one in Egypt—presumably meaning something like you know how bad it felt when you were a stranger and were oppressed, the stranger is a like you, therefore they, like you, feel bad when oppressed.

We then discussed the seventh year as a year in which, after sowing and reaping for six years, we are required to let the land go and lie fallow—and to let the indigent of the Israelite people eat what grows anyway, even though the people haven’t worked on it, and to let the animal of the field eat what the indigent leave over. We noted here a moral component to this sabbath of the land, namely, feeding the indigent. We talked about how hard it would be to give the land such a sabbath and that it would require drying some food, preserving some in oil or by burying it to keep it cool so that the people would have something to eat during the year. We noted that the agricultural idea behind the land’s sabbath, namely renewing the soil that has been depleted by growing things on it, is not mentioned. We noted specific reference to grape vines and olives, both of which will grow fairly well without care for a year. We noted that not only the Israelites but also the ox and ass get to rest on the seventh day as well as your maid’s son and the sojourner (ger) who will catch their breath (their nefesh).

The mishpatim then go in a different direction, we noted, with God exhorting us to watch ourselves in all the things God has told us, to not commemorate or let the name of other gods be heard on your lips. We noted the idea of commemorating, which is stronger than just mentioning, and therefore might mean some kind of institutional use of other gods’ names, in ritual, for example. We discussed how different our time is from that time. Then, there was risk of falling back into habits that had only just been broken. Now, we tend to open ourselves to the gods of others, to the idea that there is some validity or benefit in their gods, too. In this regard, we thought about interfaith activities. I mentioned that our time is also different in that virtually nothing remains hidden or secret, due to the nature of today’s media, so that keeping people away from other teachings is no longer the best way to keep them from falling under the spell of problematic ideas.

We then discussed the three pilgrimage holidays, Passover (here called the Feast of Unleavened Bread), Shavuot (here called the Festival of Harvest) and Sukkot (here called the Festival of Gathering). Regarding the Unleavened Bread Festival, the Israelites must eat such flatbread the seven days of the festival, and at the appointed time in Abib because it is when the Israelites went out of Egypt, and they must not come to it empty-handed (suggesting the need of contributing to the community, a topic we have discussed recently; in addition, suggesting bringing a sacrifice, so implying both contributing to God and to the community since part of a sacrifice went to God and the rest to the community) (April). Regarding the Harvest Festival, it is the festival of the first fruits and of what you will sow in the field (late May, early June). Regarding the Gathering Festival, it is at the end of the year when the Israelites harvest from the field what they have sown (late September or early October).

We noted the festivals are agriculturally organized and don’t have the theological (if that’s the right term) overlay they get later. Passover/the Unleavened Bread Festival later is about YHVH redeeming the Israelites from Egyptian bondage, Shavuot/the Harvest Festival about YHVH giving us the Torah (matan Torah), Sukkot/the Gathering Festival is about YHVH protecting us in the wilderness. We also noted that Aviv means Spring and that Passover is no longer in the month of Aviv but in Nisan.

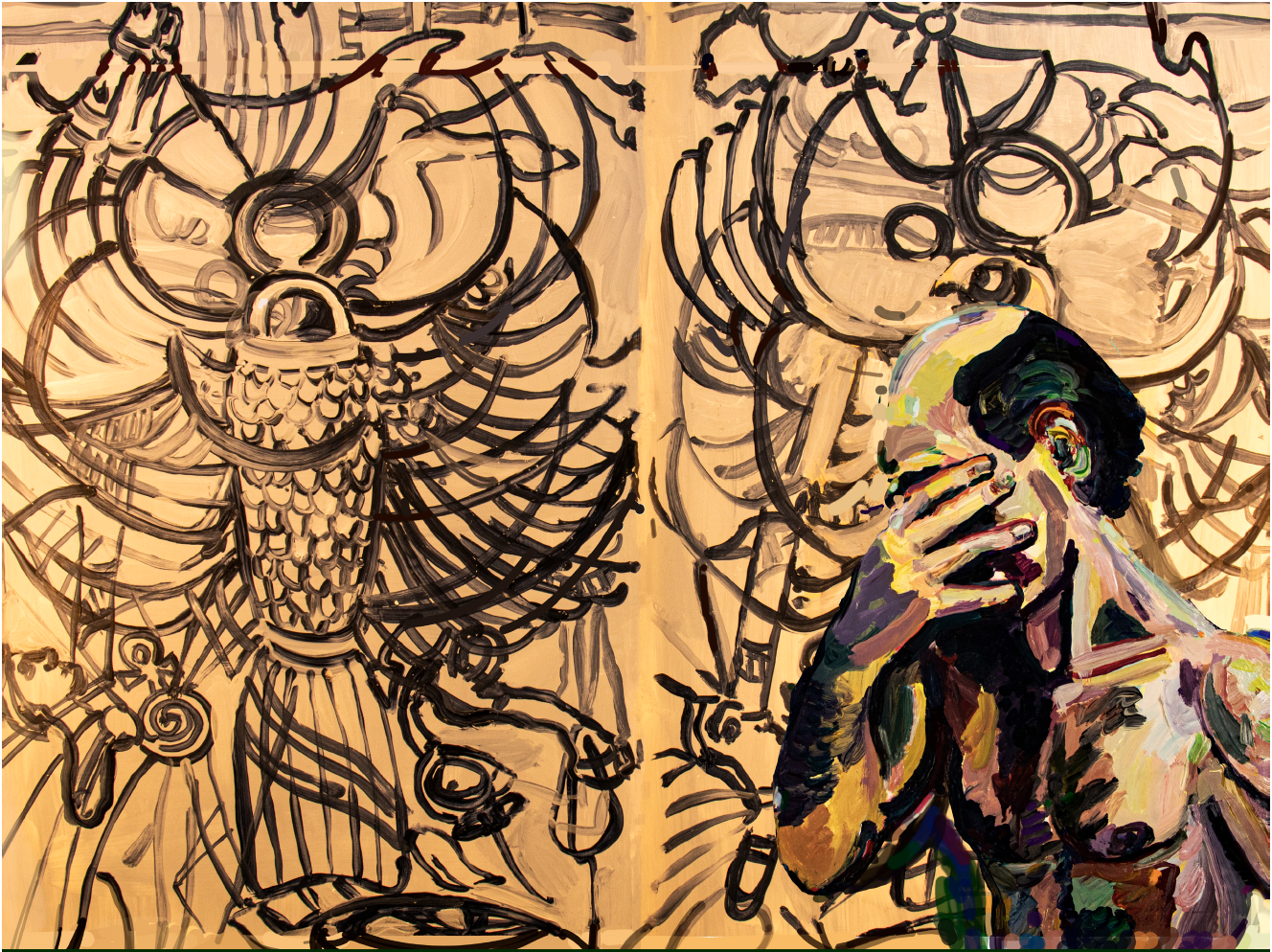

Our artwork this week is more by New York Jewish artist, Joel Silverstein (1950- ), Led by an Angel, Ex. 23:20, Num. 22:24 (above) and The Shame Bather, Ex. 19:16 (below). Led by an Angel refers to YHVH saying he will bring an angel to guard them in the wilderness (and refers to the angel confronting Balaam’s ass about which we have not yet read). There’s an excited little girl with a headband halo who might be leading some people and a blonde woman cutout from a Clairol advertisement with a figurative yellow halo behind her. The point of these two competing angels is, perhaps, to raise the question who our angel or messenger really is. The bather is a Brighton Beach bather covering his eyes. It is related to verses in which the Israelites are told they must be pure before they receive the revelation at Sinai. The contemporary bather’s hands over his eyes represents both shame, perhaps about impurity, and awe at revelation. In both paintings, Silverstein makes Torah contemporary, thus both different and the same, conveying the story by changing it.