Torah Study Date

Saturday, January 29, 2022

Verses Covered

Bereishit (Genesis) 33:10-34:2

Next Session

Saturday, February 5, 2022

Starting at Genesis 34:3

Last week we discussed Jacob asking Esau to accept his gift and the fact that, more literally, he asked Esau to accept his blessing and we wondered about that blessing, what it was (literally, it was a large amount of property but more interpretively Jacob may have been returning what he stole from Esau when he stole Esau’s blessing) and whether it could be seen simply as a gift or not. This, and other topics during the session, led us to think about more literal and less literal interpretations of passages in Torah. We discussed the relation between “ my blessing” and the French “mon salut” (which can mean everything from “my greeting” to “my salvation” to “my safety”).

We also discussed what Jacob meant when he told Esau that seeing his face was like seeing the face of God. We had a number of different ideas about that. First, it could simply be a great compliment saying that it was wonderful to see him. Or, could it mean that Jacob was afraid of him like he was afraid of God since the text refers to him seeing God’s face and being preserved (while here it refers to him seeing Esau’s face and being received favorably by him). It could also be a reference to the fact that (on some interpretations) the man with whom Jacob wrestled was Esau and seeing him was seeing God face-to-face which makes Esau equivalent to God so that seeing him is equivalent to seeing God. We discussed in general what it might mean to be face-to-face or to see someone’s face. Is it to acknowledge them (like the “thou” of Buber’s “I and Thou” or the face-to-face in Levinas), to see them as somehow divine? Does the claim indicate that it is when we do right by or act morally to another person that we are experience divinity or God? We discussed that Jacob came unarmed with property while Esau came with armed men. We discussed whether seeing Esau’s face as like the face of God was equivalent to being received favorably by Esau or whether, since God was fear-inspiring, there was a contrast between seeing his face as like the face of God and being received favorably by him. We had different opinions about it.

We discussed Jacob saying he had the whole or had everything (kol) contrasted with Esau having said that he had plenty or a great deal (rav). How could anyone have everything? We discussed the idea that he was older and, after the fight with the man/angel/Jacob/himself/God, more humble and so did not need as much. We also discussed the Gerer rabbi (also called the Sfat Emet), his idea that there is a point of the divine in everything and that whoever can connect to the divine in even very ordinary things by doing so has the whole even if they diminish their property as Jacob was about to do by giving property to Esau. We discussed the two of them going their own ways (or, more specifically, Jacob not going to Seir with Esau who seemed to want him to come but to Sukkot and then to Shechem in Canaan)–was it a strategic device because he was still afraid of Esau? was it basically what had been required of him all along (to go to Canaan)? was it just good for the two of them to stay separate, have their own space and have their own identity?—and we discussed what was going on with Esau that he seemed so much to want Jacob to come with him to Seir.

Then we began discussing the story of Dinah. Dinah went out to see the daughters of the earth. We noted that she goes to see them not to visit with them and that she has agency in going out on her own and in going to see (not be seen by) them. We noted that it was unusual for a woman to be given agency and also that it made sense that she would want to go out to spend time with other women. We tended to see her as having agency and noted that, by contrast, some commentators have seen her as a loose woman or in some other sexualized stereotypical way. We discussed that Shechem saw her (now he is the one with agency) and then did three things–took her, had sex with her, and humbled her (if “humbled” is the best translation)–and the fact that this generally is assumed to mean he raped her. We discussed interpreters who think it doesn’t mean she was raped because in later passages of the Torah an additional word is required besides the three used here for it to be punished as rape. We also discussed the possibility that in Shechem’s culture what he did might not be considered rape while in the Hebrew culture it was considered rape. We also discussed the idea that many aspects of what was considered common or normal in some cultures at that time might be considered inappropriate, denial of agency, or rape in our culture and time. We left off the discussion generally depressed by the story and also wondered why it even was included in Torah.

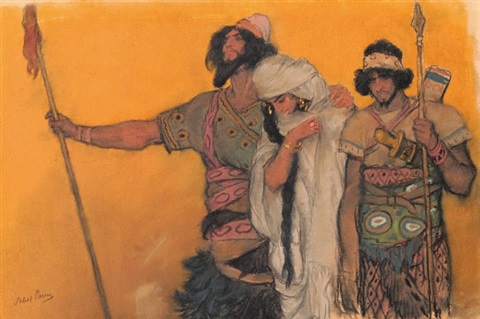

Our artwork this week is once again by Jewish Israeli painter, Abel Pann (1883-1963), Dinah (above), and Dinah and Her Brothers (below). Pann was born either in Latvia or in Belarus and later moved to Jerusalem in Ottoman Palestine. He documented the pogroms in Kishinev, studied in Paris and, after moving to Palestine, was head of the painting division at the Bezalel Academy. His life work was devoted to illustrating stories from Torah and he often used Yemenite or Bedouin women as models. His style is orientalist meaning that he portrays the biblical figures as oriental or eastern (as opposed to occidental or western). Orientalist artists often sought something in the ‘east’ they saw lacking in the ‘west’ and attempted to capture that something in their work. Orientalism is two-edged, though, because it can detail and celebrate so-called eastern cultures or it can caricature or exoticize them. Many people—including some Jews themselves—saw Jews as oriental and, depending on their orientation, either celebrated or castigated this fact.